Remembering Bunda Dorce – Indonesia’s first trans superstar

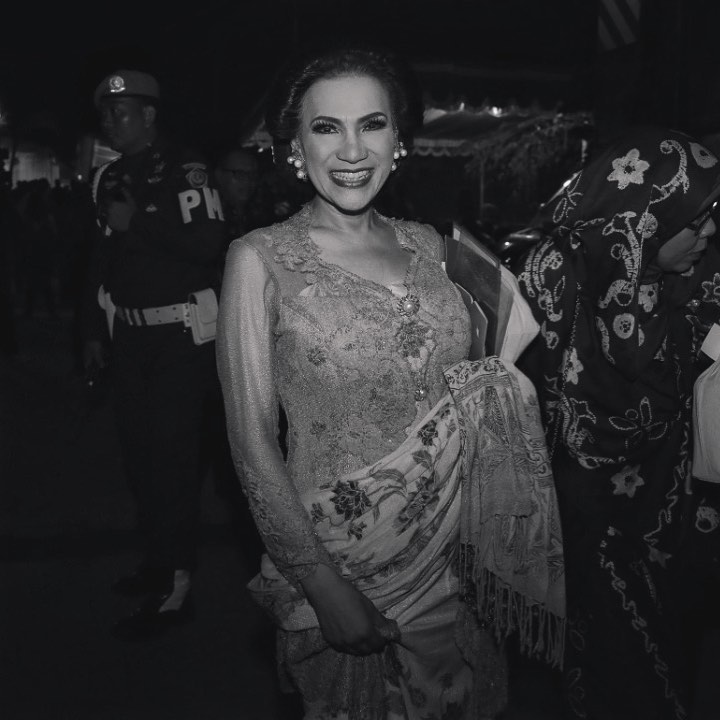

Dorce wearing a kebaya - Photo - CNN, 2018

The story of a queer’s life is not just the story of an individual, but something that is part of a larger story of the representation of queer lives in Indonesia. Queer lives are important to remember precisely because they are queer because we are so often forgotten and/or erased from history. Too often we are lost or disowned from our family trees or made invisible by state bureaucracy. Even on the rare occasions that this is not the case, we often become “lost” as the forces that form and shape our histories are reluctant to accommodate our queer identities. Instead, being queer is marked as shameful, disgraceful, or insignificant to our histories. With a hatred for our queerness, a wall is built to make us invisible. History puts on its straightest face and urges us to be forgotten. So as the sad news of a death of someone from our communities reaches us, it is also a call for us to fight against erasure. To ensure that the memories of the one who has been lost are not buried as well.

These thoughts were with me when I heard the news of Dorce Gamalama breathing her last breath on the 16th of February 2022. Her figure as a multi-talented star must not only be remembered because it is part of the history of pop culture of our country, but also because Dorce’s life story is inseparable from the history and trajectory of the LGBTIQ+ rights movement in Indonesia.

Growing up in the 90s meant that my childhood overlapped with Dorce at the peak of her star power. My childhood home was close to one of her houses, and so I would join the other neighborhood kids for an afternoon adventure to go past her home. Another house nearby was used to store all her memorabilia, like a museum to her celebrity. I remember seeing on TV some glimpses inside the house – the collections of her glamourous clothes. I also became friends with one of her neighbors, and she would share stories of Dorce’s generosity. In her properties, local women’s groups were given space to gather. In addition hundreds of orphans were supported by Dorce as a mother figure, a role she was idealized for at the time. I admire her struggle to win recognition for her rhetorical claim of “mother” in such an intensely heteronormative culture.

Dorce began her career as a member of the Fantastic Dolls, a performance group consisting of waria/transgender women. Fantastic Dolls was popular throughout the 1970s and 1980s and was led by Ibu Myrna. In the late 1960s, – when the modern LGBTIQ+ movement hadn’t yet begun in Indonesia – transgender women had begun to build a name for themselves within performance groups. These groups turned into an important foundation for the trans movement in Indonesia, leading to the formation of Himpunan Wadam Djakarta (the Jakarta Wadam Association or HIWAD) in the late 60s (sources vary, but around 1969). Other organizations would form throughout the 1970s, including some that still exist today like Persatuan Waria Kota Surabaya (the Surabaya City Waria Association or PERWAKOS) which formed in 1978 (I am aware the existence of other wadam/waria/transpuan organizations in Jakarta or other major cities in Indonesia, but I only mention these two organizations because they are the ones that I have found in the recorded history so far). Meanwhile, the gay and lesbian movement entered Indonesia with the formation of Lambda Indonesia on March 1st, 1982 in Solo, Central Java. Groups such as HIWAD and the Fantastic Dolls established the first generation of transgender activists including Ibu Myrna, Ibu Nancy Iskandar, and Ibu Lenny Sugiharto (current head of the Srikandi Sejati Foundation). Inspired by these groups, performance, entertainment and political waria groups formed throughout Indonesia, basing themselves in most major cities throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

A Fantastic Dolls performance in Ancol, Jakarta in 1986 - Photo: Tempo Magazine

At the height of their popularity in the Fantastic Dolls, Ibu Myrna was said to have given Dorce her performance name by which she is now known. Dorce herself would adopt the name “Gamalama” in the early 1980s after visiting mount Gamalama in Ternate alongside Benyamin Sueb (an actor who famously depicted Betty Bencong Slebor in 1978). Her last name, “Halimatusadiah”, was taken after Dorce completed the Hajj in 1990.

The 1980s were challenging years for Dorce as she communicated her gender transition in almost all aspects of public and cultural life whilst continuing her entertainment career. This encapsulated her most amazing and most significant success, and is something that we as a queer community should respect her for. The fact that she achieved this cultural victory of recognition of her transition whilst continuing the struggle through her career in the entertainment world.

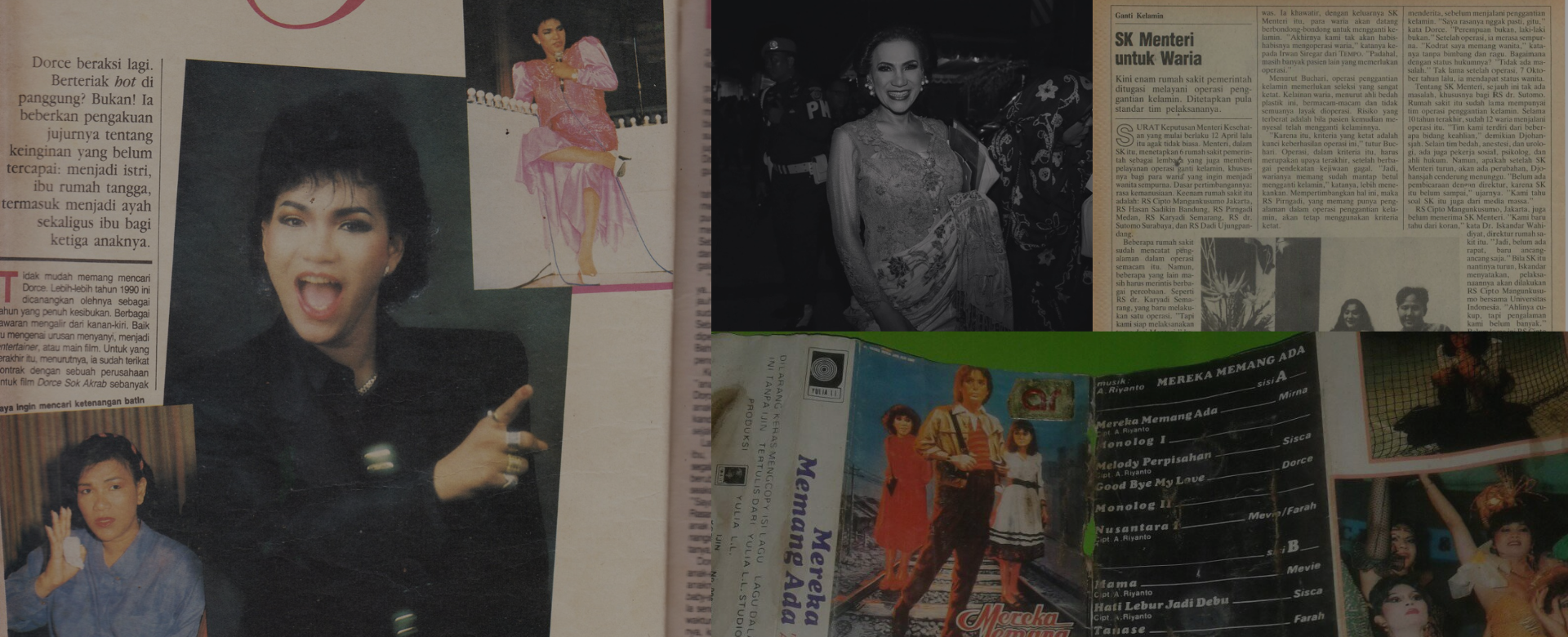

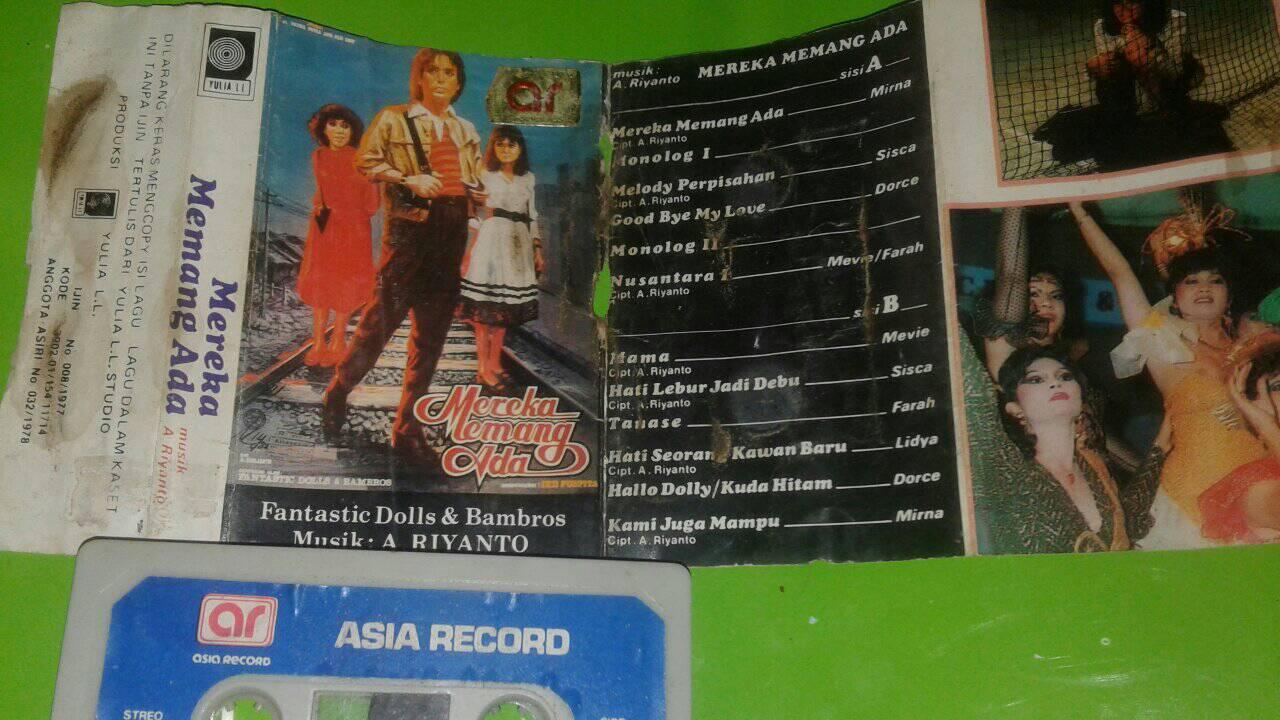

Chenny Han, an alumni of Fantastic Dolls, often likened Dorce and Ibu Myrna to perfectly complimenting dishes of entertainment. At this time Dorce was also involved in a film that was about the experience of trans women, and had trans women in the cast – Mereka Memang Ada (1982). The popularity of the film is shown by the release of the soundtrack on cassette, on which Dorce contributed two songs. It was one year after the release of this film that Dorce began her medical and surgical transition. This decision was made through a religious contemplation and contact with God, a moment which further solidified her intention to live publicly as the woman she was, and undertake surgery. Although initially rejected by her doctor, Dorce continued seeking treatment until she located the plastic surgeon Prof. Djohansjah Marzoeki.

The motion picture soundtrack for Mereka Memang Ada

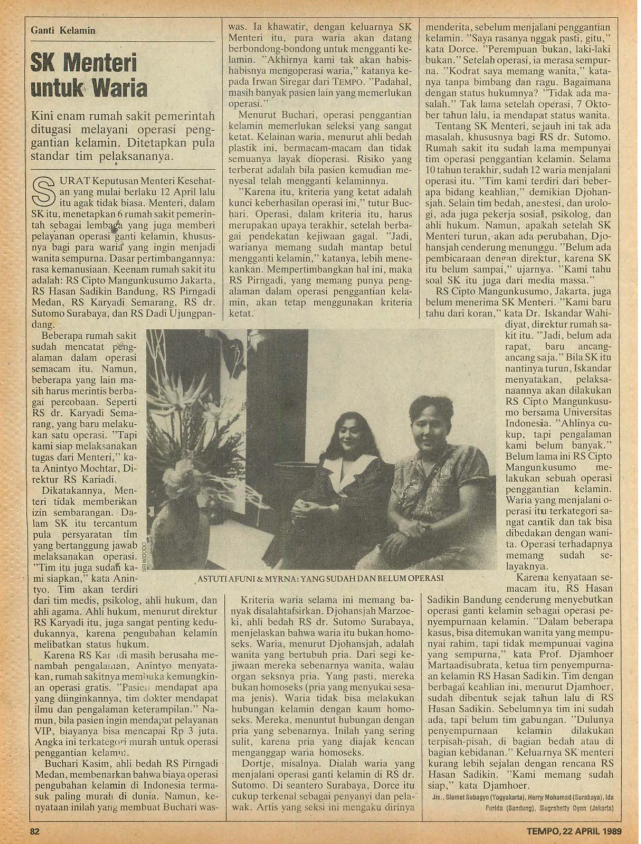

Prof. Djohansjah Marzoeki who performed the surgery stated (in Angin Malam episode 42 “Dorce’s Journey to Plastic Surgery”) that alongside him there was a team consisting of obstetricians, internalists, geneticists, psychiatrists, psychologists and others to ensure “the candidate (Dorce) is not pretending or imitating, but it is a desire that is driven from her, by her determination which is complete”. This was not the first time that this surgery was performed, but the huge public spotlight at the time changed the views of many people, including the doctors/experts that Dorce managed to convince.

An article exploring surgery for trans women from Tempo Magazine in 1989

After undergoing the surgery Dorce often met curiosity about her body with a quip or a joke. Dorce often praised herself for being pretty or sweet and would say she had “no regrets, even if my “bird” is cut off”. When speaking to cishet women, she would say “you (cis women) might be able to have children, but I can give pleasure” – these are just a few quotes that I remember from watching her.

Not stopping at her social and medical transition, she used her newfound backing from the medical experts to seek legal recognition of her gender. “I want to be recognised by the state” she said on a TV show alongside her surgeon Djohansjah. In addition, she sought the support of Islamic scholars to help challenge Islamic scholarship that were antagonistic to her transition. Although Vivian Rubiyanti was the first indonesian trans women to successfully access medical and legal gender transition in Indonesia (her story was documented in the film Akulah Vivian in 1977) it may have been Dorce who was the first to emphasize the religious aspect of her transition in Islam, and have that highlighted within public discourse. For her, this was an important part of her transition given her own faith, the faith of a majority of Indonesians and the role that Islamic religious law plays within the Indonesian legal system – especially marriage law. In addition to approaching Islamic scholars and leaders, Dorce responded to doubts about her piety as a muslim women through acts of charity – the construction of Islamic boarding schools and mosques. In the mid-1980s, Dorce was formally recognised by the state as a woman. Shortly after she married, and took the title “hajah” in recognition of her pilgrimage to Mecca as a woman. She raised 3 children, and supported thousands of orphans. Although often the target of public hate campaigns and ridicule, she also managed to build a strong fan base who enjoyed the joy she brought to public entertainment and her immense generosity with her newfound wealth.

She said “I was reborn” after returning from her pilgrimage to Mecca.

After the two of her starring films Dorce Sok Akrab (1989) and Dorce Ketemu Jodoh (1990) became blockbusters, Dorce gained superstar status within Indonesian pop culture – as an actress, singer, songwriter, comedian, TV host and many other roles. Her face graces the small screen throughout the 1990s. She starred in many films, soap operas and talk shows whilst maintaining a successful music career. Dorce even set an Indonesian music record for releasing 9 albums within five months. Eventually from 2005-2009 she would host her own talk show: The Dorce Show. The show itself was successful and was even nominated for best talk show. It was from hosting this show that her final moniker ‘Bunda Dorce’ would be popularised.

However, after the Reformasi movement in 1998 – or to be perhaps more precise, after the 2009 election – there was a significant rise in religious fundamentalism and anti-”LGBT” populist movements. From this moment the LGBTIQ+ movement began to face situations unanticipated animosity and often became the target of religious fundamentalist movements. However, as we know Bunda Dorce had spent considerable effort in showing her piety as a muslim woman.

After her talk show was cancelled in 2009, Dorce’s personal life often became the subject of discussion by those promoting conservative interpretations of Islam. She herself – with all her achievements as a performer and muslim woman – often faced challenging situations with the increasing targeting of the “LGBT” community as cultural scapegoats by conservative clerics, politicians and officials in the era of liberal democracy. Gradually, Dorce’s figure dimmed from the public sphere alongside a decline in her physical health.

Dorce wearing a hijab

In fact, towards the end of her life, Dorce was vilified within certain parts of public media in Indonesia. Conservative clerics did not hesitate to make the life and figure of Bunda Dorce a target in order for them to get public attention.

However, in these times Bunda Dorce never allowed herself to be a submissive victim. Instead her life story is a significant and powerful reminder of a trans woman who was able to excel in so many fields, and sparked the dreams and aspirations of many queer people, especially waria/trans women across Indonesia.

We will continue to remember her wise words – that “perfection belongs only to Allah” – not doctors, experts, ulama, ustadz, politicians nor the state.

Through this essay, QIA wants to call on you the reader who might have materials that reflect the life of Bunda Dorce (photos, articles, books, tapes, albums etc). Her memory has left such a extensive mark on Indoneisa, a mosaic that has enriched the histories of queer people and our struggles. Through the archiving and recording of the lives of figures such as Bunda Dorce (and the many queer icons throughout Indonesian history), we hope to inspire resistence against the pressure to be quiet, forgotten, or erased in our national history.

This is the first of a series of essays we will be sharing from guest writers.

Nurdiyansah Dalidjo

Nurdiyansah Dalidjo is a queer writer. His latest book, entitled Rumah di Tanah Rempah, explores various intersectional topics about the history and the context of colonialism in Indonesia from the perspective of a queer. His essays exploring various LGBTIQ+ themes can be read here.